[Updated August 2021] You’ve found your way to post #4 of my series of articles on the Urban Alaskan, written for my non-Alaska friends, where I talk about how my day to day experience is exactly like yours, mostly, except for the moose and timezone. If you want to catch up, you can see post #3 here.

[Updated August 2021] You’ve found your way to post #4 of my series of articles on the Urban Alaskan, written for my non-Alaska friends, where I talk about how my day to day experience is exactly like yours, mostly, except for the moose and timezone. If you want to catch up, you can see post #3 here.

August marks the anniversary of when my brother-in-law went missing, more than 20 years ago as I write this. It was a beautiful sunny day, and for Seward, AK, that’s a rare thing. Actually, the whole summer had been a nice. I think that was the same summer it hit 90 in downtown Seward and the pavement buckled, something not repeated until the summer of 2019. Stewart, my wife’s twin, decided to go to Bear Lake for a spin around on a jet-ski on his day off. I no longer recall if he was a deck-hand on a fishing boat or was doing guiding over in Bristol Bay at that point. Anyhow, somewhere in there things took a tragic turn. Nobody knows what actually happened. He had a couple of friends with him, but they were otherwise occupied or out of sight when the incident occurred. At this point it’s all rather irrelevant.

Alaskan Lakes are mostly very, exceptionally, cold. Typically, the temperature of an Alaskan lake isn’t a great deal higher than freezing. With water that cold, hypothermia happens so quickly you might only have a couple of minutes. Yes, you can survive for a surprising amount of time in some of these lakes, but as a rule, you’d better be wearing a life preserver. In the vast majority of circumstances, if you fall into the water, you’re not going to have the strength to swim to shore if you’re any distance in at all. There are exceptions to this, especially around Anchorage, but I can also tell you that swimming for me as a child meant wading into your knees and completely losing feeling for a few minutes. This also made my boy scout swimming test absolute hell because I was so terrified of the cold water, I couldn’t jump in for the swim, even though the water was cold but not deadly. At this point, folks from the lower-48 might conclude that I’m exaggerating and it doesn’t happen that fast, but it does. Falling into a lake without a life preserver, even for an excellent swimmer can be a death sentence. Add physical injury to that and your odds of survival are about as good as jumping from a very high place. Because of the icy water, everything sinks too. So, not only did he go missing, he stayed missing for days before they were able to find him at the bottom of that unforgiving lake.

I know these sorts of accidents happen everywhere. It’s the nature of being human – shit happens and sometimes we pay for it with our lives. However, nearly everyone who has lived up here for any significant amount of time knows someone who has died attempting to enjoy the outdoors (or at the very least has a 1-off). Sometimes it’s an accident that could’ve happened anywhere – jet ski accident or the like. Other times it’s a rare accident. For example, I knew a guy from high-school who died in an avalanche a few years after we graduated. Deadly bear maulings, even very close to Anchorage, aren’t unheard of. There’s also the classic story of the person who got stuck in the mud in Turnagain arm and drowned from fast moving tides. The real story comes from north of Anchorage involving a soldier and his friends. On top of that, there are plenty of stories with people going off on what we all trick ourselves into believing is an easy day-hike alone only to suffer an injury and subsequently die of exposure. In 2021 a woman went missing not far from Palmer after being charged by a bear. They searched two days and didn’t find her. In her case, she made her way to a main road and survived. However, this illustrates that even close to population, you can go missing badly enough that teams of searchers may never find you.

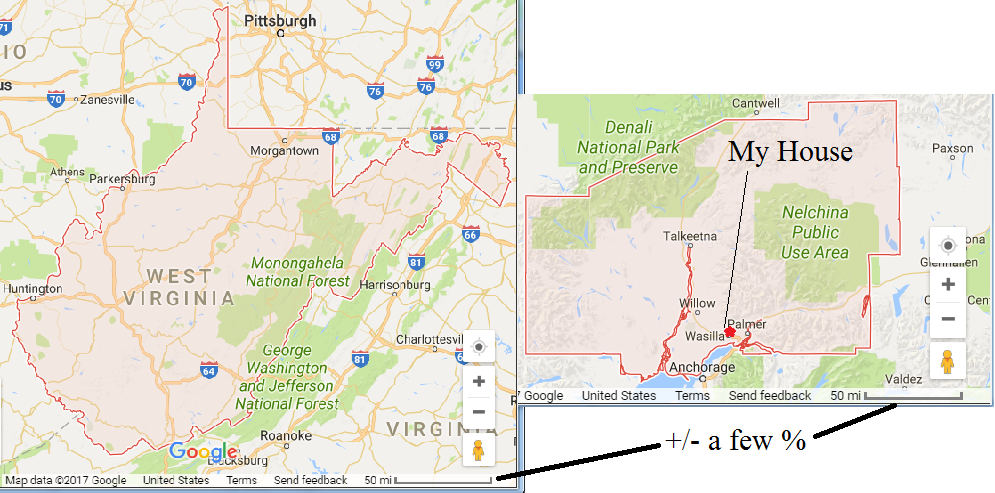

Now, I’ve said all of this but I don’t think the exotic ways people die up here is actually particularly unique. After all, nobody was ever eaten by a gator up here or taken up in a tornado. What is unique is the ultra-low population densities. So, when something does happen. It can take days or weeks before someone happens across you, even when they’re looking for you. What’s more, when this sort of thing happens, odds are that your extended family is very far away indeed, so pulling together in that family way is difficult to impossible. I think this is really what gives urban Alaskans the sense of remoteness that we probably don’t deserve. After all, if I can go have lunch at a Subway sandwich shop and in twenty minutes, ON FOOT, be so remote that even after years of searching nobody could find my mangled body at the bottom of that ravine, it can set up some pretty confusing dichotomies. On one hand, wilderness, on the other, city life. It’s weird and dangerous.

I’d like to draw your attention to the averages for January and December. Wasilla is pretty mild on average compared to all three. It’s also milder than all three in the summer time, but still above freezing 🙂 These data were sourced from (weatherbase.com – this data has some issues, but it’s generally ball-park). This graph illustrates the fact that cities deep inside a continent exposed to more extreme weather than those near the coast, even northern cities. While it’s easy to forget that Wasilla is near the coast, Anchorage is a port city and even though we’re 180 or so miles from the expansive gulf of Alaska, we still experience the moderating effect of the ocean.

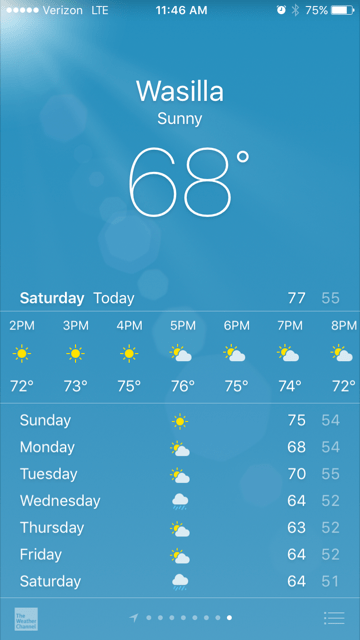

I’d like to draw your attention to the averages for January and December. Wasilla is pretty mild on average compared to all three. It’s also milder than all three in the summer time, but still above freezing 🙂 These data were sourced from (weatherbase.com – this data has some issues, but it’s generally ball-park). This graph illustrates the fact that cities deep inside a continent exposed to more extreme weather than those near the coast, even northern cities. While it’s easy to forget that Wasilla is near the coast, Anchorage is a port city and even though we’re 180 or so miles from the expansive gulf of Alaska, we still experience the moderating effect of the ocean. The truth is that summer is about as nice as it gets. It’s light all the time and the temperature is rarely uncomfortably hot in a way that most folks from the lower-48 would understand. The highest temperature ever recorded in Alaska was 100F in Fort Yukon. It more regularly gets into the 90s with an average of 2-4 days per year in places like Fairbanks hitting temperatures in the 90s. It’s much more common for the temperature to be a bit on the cool side. Over the weekend we (Wasilla) soaked in temperatures pushing 80F. Pretty mild by anyone else’s reckoning, however keep in mind it so infrequently reaches the 80s, that we don’t have A/C. It makes being inside the house borderline unbearable.

The truth is that summer is about as nice as it gets. It’s light all the time and the temperature is rarely uncomfortably hot in a way that most folks from the lower-48 would understand. The highest temperature ever recorded in Alaska was 100F in Fort Yukon. It more regularly gets into the 90s with an average of 2-4 days per year in places like Fairbanks hitting temperatures in the 90s. It’s much more common for the temperature to be a bit on the cool side. Over the weekend we (Wasilla) soaked in temperatures pushing 80F. Pretty mild by anyone else’s reckoning, however keep in mind it so infrequently reaches the 80s, that we don’t have A/C. It makes being inside the house borderline unbearable.

One winter, in particular, I think it was 1998/1999, or possibly the year after, when I lived in Fairbanks it did not get warmer than -20F for something six weeks straight. It was routinely around -35F that year and I believe it reached as cold as -45F or possibly pushing -50F. The truth of the matter is that anyone living in a northern US state, like Minnesota, will have experienced similar temperatures. I think the main difference is that in Fairbanks those temperatures can linger for weeks. What nobody ever tells you about those temperatures is just how fast you are robbed of heat on exiting a building. One moment you’re not particularly cold, the next, you’re frigid. The other thing is how the soles of your shoes freeze so that when you walk into a building you have to proceed with duck-footed caution for a few moments, lest your feet shoot out from underneath you. The last interesting thing to note about excessive cold is the fact that you simply can’t touch anything metal with your bare hands. I mean you can, but it’s painful. After living in Fairbanks, you become conditioned to slipping your hand into your sleeve to grasp any door handle. Even in Maryland when things got ‘cold’ I found myself grabbing perfectly warm door handles with my hand in my sleeve out of habit. In Wasilla some years, the wind can be so bad, it rips satellite dishes from their mountings on the roof and piles snow six feet deep in the driveway. I recall one particularly bad year where I pulled up to an intersection to find the signal gone, a lonely strand of wire dangling to the ground in it’s place. So, yes, winter can be a hellish experience that matches or exceeds the expectations you might have from Johnny Horton or Jack London, but it’s not all bad.

One winter, in particular, I think it was 1998/1999, or possibly the year after, when I lived in Fairbanks it did not get warmer than -20F for something six weeks straight. It was routinely around -35F that year and I believe it reached as cold as -45F or possibly pushing -50F. The truth of the matter is that anyone living in a northern US state, like Minnesota, will have experienced similar temperatures. I think the main difference is that in Fairbanks those temperatures can linger for weeks. What nobody ever tells you about those temperatures is just how fast you are robbed of heat on exiting a building. One moment you’re not particularly cold, the next, you’re frigid. The other thing is how the soles of your shoes freeze so that when you walk into a building you have to proceed with duck-footed caution for a few moments, lest your feet shoot out from underneath you. The last interesting thing to note about excessive cold is the fact that you simply can’t touch anything metal with your bare hands. I mean you can, but it’s painful. After living in Fairbanks, you become conditioned to slipping your hand into your sleeve to grasp any door handle. Even in Maryland when things got ‘cold’ I found myself grabbing perfectly warm door handles with my hand in my sleeve out of habit. In Wasilla some years, the wind can be so bad, it rips satellite dishes from their mountings on the roof and piles snow six feet deep in the driveway. I recall one particularly bad year where I pulled up to an intersection to find the signal gone, a lonely strand of wire dangling to the ground in it’s place. So, yes, winter can be a hellish experience that matches or exceeds the expectations you might have from Johnny Horton or Jack London, but it’s not all bad. My point is that yes, it can be very cold and dark in the winter, or cold and damp in the summer, but on the whole, it’s not actually worse than any northern state, and in my opinion the summers are nice enough to make up for all but the most painful winter experiences. There is nothing at all like sitting outside under the midnight sun around a fire sipping a cold one.

My point is that yes, it can be very cold and dark in the winter, or cold and damp in the summer, but on the whole, it’s not actually worse than any northern state, and in my opinion the summers are nice enough to make up for all but the most painful winter experiences. There is nothing at all like sitting outside under the midnight sun around a fire sipping a cold one.